Hedge Fund Performance 2009 09

Hedge Fund Performance 2009 09

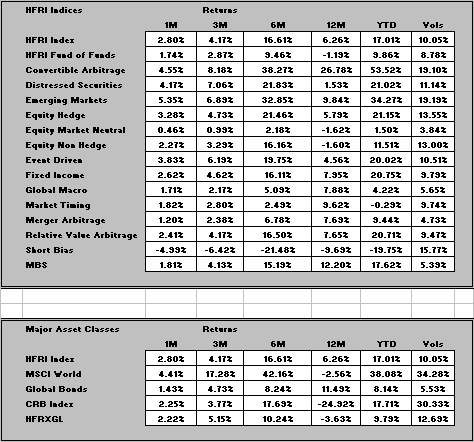

Hedge funds as represented by the HFRI returned 17.01% year to date. In the same time period, the MSCI World returned 38.08% YTD. Global Bonds measured by the Barclays Global Bond Index (the old Lehman Agg) gained 8.14%, and the CRB Index (Commodities) gained 17.71%. Adding more granularity to the numbers, the volatility of the HFRI was 10.05%, the MSCI 34%, the Barclays Global Bond 5.5% and the CRB 30%.

Convertible arbitrage led the pack with a 53% YTD gain. Its not clear what the arbitrage is. Rising equity markets, tightening credit spreads and renewed issuance are driving long only performance to an extent that sidelines the need to hedge. And with the numbers, its not clear how much hedging is going on. Recent performance, 1 month and 3 month has been consistently robust.

Emerging market funds also performed well with a 34% YTD return. Given the performance of Asia and LatAm, its not surprising that these funds have done well. An accidental net long bias would quickly have turned into a windfall profit.

Equity hedge has done well as well returning 21% YTD. Volatility has been quite high, evidence of a net long bias in aggregate as some managers chased rising markets. Equity market neutral strategies’ performance was instructive. YTD they have gained a paltry 1.5% with a volatility of 3.8%. This year’s equity market volatility, the decline in the first 2.5 months followed by the strong rebound has been characterised by liquidity, central bank policy, macro economic recovery, market psychology, and a reversal of risk aversion. So, of the non market neutral managers, how much alpha have they been generating? How much alpha could they possibly generate under the circumstances? When will it become a stock pickers market again?

Distressed debt strategies returned 21%. It is not clear if this return is due to the specific execution of the strategy or if it is a collateral consequence of spread tightening and rising equity markets on a predominantly long biased strategy. The volume of workouts is still slow compared to the acceleration in defaults. There is risk of volatility in this strategy and certainly ample opportunity for later entry points.

Event driven strategies returned 20% YTD but then event driven strategies encompass a host of strategies, so generalization is not useful.

Merger arbitrage underperformed with a 9.44% YTD performance albeit at volatility of 4.7%. Developed market deals have been patchy. Deal flow has slowed considerably, particularly in value. Apart from a few high profile deals, Cadbury Kraft, Marvel Disney, Liberty Direct, Sun Oracle, much of the action has been smaller and cross border, EM outbound. The deals done in the current environment carry far less uncertainty and risk. Risky deals are unlikely to come to market at all. While deal spreads have been wider than usual, there has been a dearth of hostile, complex deals where the returns usually come from. Leverage has also been scarce even for friendly deals. The result is lower returns but at lower risk.

Global macro, the favoured strategy at the end of 2008 for its resilience and performance in a difficult year (for everyone else), returned 4.2% YTD in a lacklustre performance. Especially in the context of a 5% volatility. This is not surprising in one sense but surprising in another. Investors chase returns. The first half of 2009 saw an increase in the number of potential start ups in Global Macro to catch the impending cascade of capital, which never came. It all ended up being funnelled into a few established, high profile, large scale funds. The glaringly easy trades of 2008 were no longer. It was to be expected that global macro would struggle. On the other hand, many interesting opportunities exist. Confused, prevaricating central banks, uncertain inflation expectations, confused, prevaricating Treasuries, a restructuring in the trading market for sovereign debt, particularly hard currency sov debt, is ideal for macro. So, why the poor performance at the aggregate level? Mediocrity. The good quality managers continue to take advantage of a very interesting macro environment.

Fixed income arbitrage has had a good year. 20% YTD. The drivers for their returns are very much related to the performance of global macro. Confused, prevaricating central banks, uncertain inflation expectations, confused, prevaricating Treasuries, a restructuring in the trading market for sovereign debt, particularly hard currency sov debt. The problem lies in the benchmark index methodology which is self reported and thus self classified. The macro index is contaminated with CTAs which sometimes classify themselves as Macro.

CTA’s have had a very tough year after a sometimes spectacular 2008. In 2009, they returned about 0% with nearly 10% volatility. I do not have the mathematical or statistical faculties to pretend to understand CTAs but it is rather disappointing to see a strategy so much in demand at the end of 2008 suddenly fall out of favour so quickly. I suppose in the absence of information, performance is the main determinant of investor demand.

On a risk adjusted basis, the MBS funds are hard to beat. 17.6% YTD with 5.6% volatility. Its hard to decline an invitation to feed at the trough filled by government monies.

Before we leave this, notice the difference in performance between HFRI and HFRI FOF. HFRI is an index of hedge funds while HFRI FOF is an index of funds of hedge funds. There appears to be a vast underperformance by funds of funds that cannot be simply explained by the additional layer of fees. Applying 1 and 10 fees on top of the HFRI still gets you to 14% YTD. The volatility of the funds of funds index, however, is 13% lower than that of the hedge funds index. If that is explained by cash, then the funds of funds index should still return around 12%. If we assume a much higher level of cash, say 24%, then we get to a ballpark of 10% YTD for funds of funds.

This appears to be what has happened. In the wake of the 2008 crisis, funds of funds raised more cash than they needed. They could not know how much cash they would need to meet investor redemptions and had to be conservative.

All this together gives us an interesting picture of the hedge fund industry, the performance of strategies, the expectations and behavior of investors and funds of funds in their role as intermediaries and pooling vehicles.