Where is the S&P500 Going? Another Unscientific Look

Betting, Outright Gambling on the Stock Market

On 19 Feb 2009 I wrote an article arbitrarily calling for the S&P 500 to bottom at 650. Where is the S&P500 Going? An Unscientific Look. It bottomed out on 9 Mar 2009 at 676.

Prescience? No. Intelligence? No. Skill? No. Absolutely none of the above. Luck? Yes. Luck. Nobody consistently calls the market. Nobody. Period. But we can play a very entertaining game of Guess Where the Stock Market is Going. It costs very little, unless you put money behind it, in which case it either makes a lot or it costs a lot. I had the luxury of buying selective Asian small caps in late February based on my own shot in the dark GUESS of where the market was going and that’s nice but not something I would count on as a long term means of feeding my family.

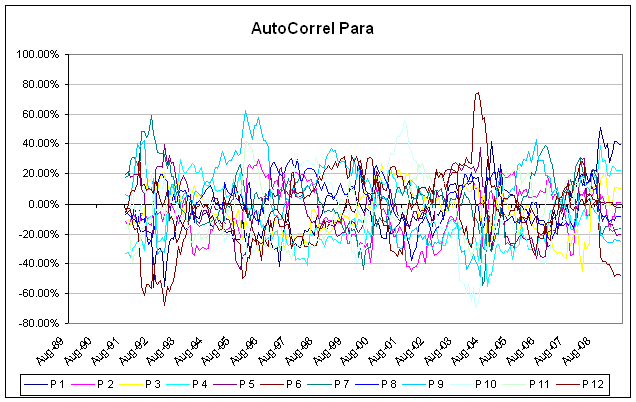

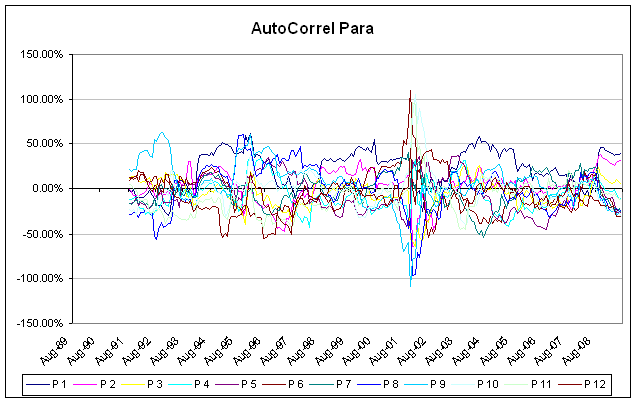

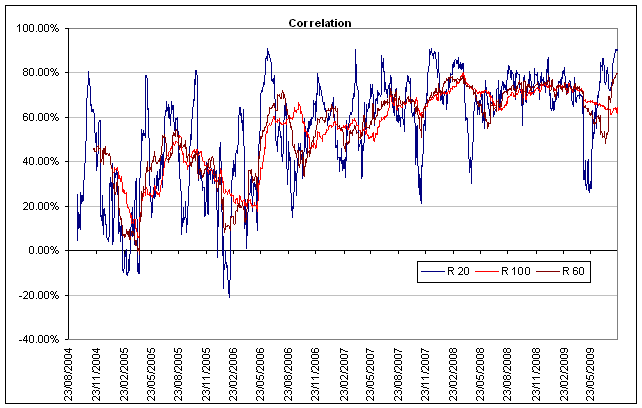

So, here is the chart I was looking at in February, updated to 7 Sep 2009.

The S&P 500 at 1016, 4 Sep 2009

The easy call is over. At 780 with market sentiment highly distressed it is very easy to call a further 100 points decline. I’ve done that and put money behind that call. Was I sure? Hell no. If I did I would have mortgaged the wife and kid to do the trade. Instead I took small, controlled, well researched positions to make up for my fear and uncertainty at the time. That’s what you do when you are not sure. And that is to add to the painful investments I made too early in 2008. Now what? The market has rebounded over 50%. Who know’s where the market will go. But looking at the chart, a retracement to 750 is not improbable. Here is how it would look, visually without all the cool statistics and quant indicators that only PhD’s and finance types understand…

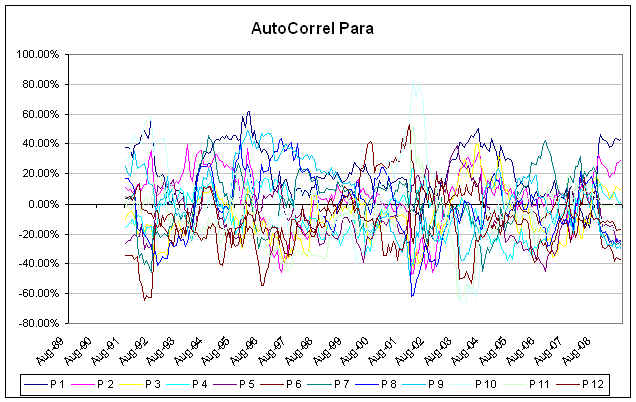

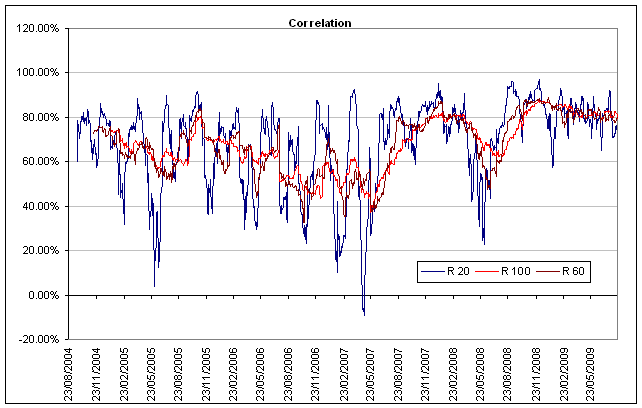

The S&P500 at 750

It doesn’t look ridiculous, it doesn’t look out of this world. And will not look out of this world if it trades within a range of 800 – 1000. It would look a bit volatile if it traded up to 1400, but it wouldn’t look ridiculous there either. Do I think it will get there? No. I think 800 is more likely. Why? Fundamentals have improved but not so much that they justify stock market prices at even current levels.

How about if we debase all currencies so that relative FX prices remain fairly constant but the prices of stuff, that is goods, services, resources that are found or grow in the ground, rise. What then? Well, stock prices are likely to be supported as well, and the same goes for bond prices. That’s what happens when the yardstick is shortened.

When will markets head south towards 800? Later in the year is my guess. The market is being sustained by skeptics and bears and until the marginal buyer is exhausted, the market can and is likely to keep rising.