Open and Shut: Immigration

Open:

Immigration is good for the economy. Unless the allocation of resources is already optimal everywhere, a redistribution of resources (human in this context) can increase the wealth and welfare of the collective. Workers moving from a poor country to a rich one become more productive as they are combined with more and better capital, management and infrastructure. Workers from rich countries moving to poorer ones bring experience and expertise which they can impart to the local labour force.

Immigration is a basic human right. The location of a person’s birth is a matter of chance and there is no moral justification for compelling someone to stay where they are. People fortunate enough to be born in rich countries have no moral justification for excluding people from poorer countries.

Special cases: Immigration may be due to natural disaster, war, persecution or economic duress. Such immigration is supported on humanitarian grounds.

Shut:

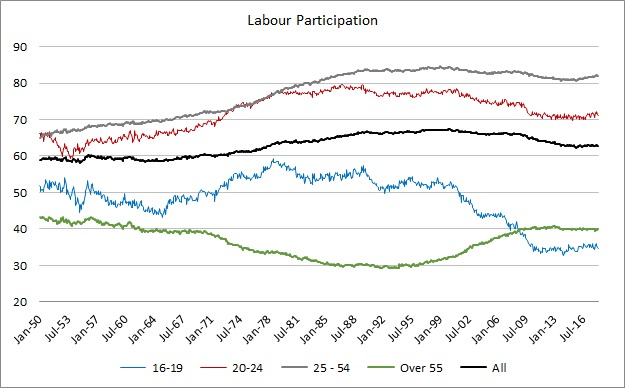

Immigration displaces local employment and depresses wages.

Immigration creates increased competition for resources, public goods and social welfare. Indirectly, it also increases budget burdens and the national debt.

Immigration increases inequality.

Immigration raises issues of cultural integration which can lead to social friction, increased crime and pose security risks.

Overcrowding and population density. There is an optimal population density which maximizes welfare.

Open and Shut:

The pragmatic view is that some immigration is unavoidable, necessary and desirable. Where there is a shortage of labour skilled or otherwise, immigration can be a useful way of alleviating shortages. Immigration can even be encouraged in specific industries, sectors, demographics. Immigration can also be encouraged to import specific types of demand, say to attract capital and demand for financial services or luxuries.

The pragmatic view is unlikely to welcome all types of immigration, only those accretive to the incumbent population and economy. It would also take into consideration its existing endowment and supply of public goods, resources and land to avoid over-competition and over-crowding.

Opponents to immigration raise some difficult questions. Immigration is disruptive. While in aggregate, the economic benefits are clear and the critiques, raising unemployment, lowering wages, increasing inequality, have mostly been debunked, this is only true in aggregate. Immigration does create unemployment and depress wages, in specific parts of the economy. At the same time, they bring benefits to employers and consumers by lowering wage costs, and dampening inflation. Averages and aggregates do not reveal detail.

Beyond economics, opponents of immigration raise other, less tractable questions.

The first duty of a government is to its citizens, not to immigrants. If the majority of citizens oppose immigration, the government cannot ignore them. This risks making immigration a highly polarizing issue.

Welfare systems have been built over time and, as underfunded as most of them are, they represent the savings of generations of citizens. Can immigrants draw on these same reserves having not yet contributed to them? Can their future contributions be counted on? Immigrants may be itinerant and thus a burden on the system or they can be sticky and increase the tax base thus funding future generations of welfare.

Is a reasonable level of population density also a basic human right and is overcrowding a valid reason to moderate immigration? How dense is too dense?

How should a country balance the rights and obligations of citizens and incumbents against immigrants?

Even if we accept that sanctuary has priority over most other considerations, to what extent should immigration be allowed in the context of space and resources?

The question of immigration is unlikely to be settled. The current distribution of people across the planet is the result of millennia of migration as the species sought out ever more hospitable living places. Once the barriers were natural or physical but today they are political and man-made. At the same time, many of the features that make a place attractive are man-made, made by earlier settlers, who understandably attach a cost to that effort and enterprise. As incumbents, they have rights to who can join their community. But also we have to recognize that this planet is not entirely ours. To some extent, we share everything on the planet, the rewards and consequences, whether we realize it or not.

The zeitgeist is increasingly anti-immigration to the extent that even the pragmatic view is insufficient. Unless we adopt at least a more accommodating position, policy will be more restrictive than is economically efficient and the price will be paid in real wealth and welfare. But we need to move beyond even this pragmatic view. The benefits of immigration go beyond economics. When properly managed (with proper integration with the existing community), immigration fosters cultural understanding and empathy. It is hard to put a value on such qualities but in a world that is growing more contentious and less cooperative, it has value.