The ECB is in a difficult position.

The European economy has long been bogged down with structural impediments and the challenges of a partially unified single market. Yet in 2017, the European economy experienced a significant pick up. PMIs surged and GDP growth recovered to levels before the 2011 European crisis. Some of the strength has come from a rebound in international trade after European exports picked up noticeably in the second half of 2017 after 6 years of stagnation. Another source of strength has been QE. The ECB balance sheet has increased at over 2.3 trillion EUR since it began buying bonds some three years ago. The weakness of the EUR helped in 2015 and 2016.

Now, however, things are beginning to turn. The Eurozone manufacturing PMI which rose from the low 50s to over 60 has recently retraced sharply to below 57. Industrial production has shown a similar pattern. The ECB’s asset purchases have been extended to September but sizes have been halved from 60 to 30 billion EUR. International trade has begun to slow, and this before material action on tariffs. The strength of the EUR is another complication. Once trading at 1.03 it rallied to over 1.25 and has settled around 1.22. EUR strength will act as a brake on the economy especially since Europe is heavily dependent on trade (which represents over 80% of GDP). And as Europe imports over half of its energy requirements, 90% of its oil, 69% of its natural gas, 42% of its coal and 40% of its nuclear fuels, rising energy prices are a tax on the European economy.

The task facing the ECB is a daunting one. It has begun to slow its purchase of bonds but it hasn’t yet begun to stop accumulating assets although has signalled that it will do so in September 2018. It has not yet raised interest rates and maintains negative deposit and zero repo rates. Its accommodative policy tools are fully deployed and while the economy is still growing that growth has begun to slow. If Europe tips into recession, it has little ammunition left to fight it.

For now, the slowdown is moderate and recession risk is low. There are, however, a couple of sources of risk.

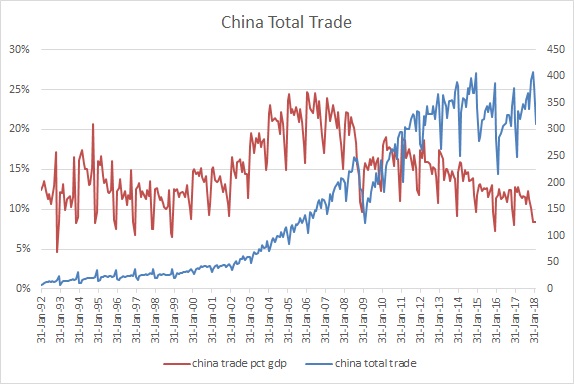

The risk that the trade war resumes is significant. Apart from a general state of strategic competition, trade wars are politically expedient. For the last 5 years China has turned its focus to the domestic economy while the US has re-shored manufacturing (not to mention discovered a lot of oil). Both countries are now less dependent on trade than before despite being the main protagonists in the war. Both will calculate that they have less to lose than the other, and other innocent bystanders, in an escalation of hostilities. Trump may require the diversion for the mid-term elections while Xi, despite recently consolidating power may choose to appease a proud and nationalistic people. He may have won the war within the Party but may still need to win hearts and minds. Europe could be collateral damage in a trade war not of its making. It could choose a side, Europe exports twice as much to the US as to China, but future growth is another consideration. While the US builds walls, China builds bridges and would appear to be a more willing and constructive partner. Europe’s history and scale mean that it is more likely it will be a third player in a trade war, fighting its own corner.

Political risk in Europe has receded in the eyes of the market but remains a significant factor. Emmanuel Macron presses on with his reform agenda despite a series of rail strikes that will last into the summer. His federalist vision is not shared in Germany where a grand coalition governs. If only it were a strong coalition. The CDU/CSU and SPD command but 53% of the vote, while the far right AfD has 13% of the Bundestag seats. Italy as yet has not formed a government since elections in early March produced a hung parliament dominated by populists and Eurosceptics. Spain operates under a minority government and faces secessionists in northern Catalonia. The ECB’s policy will likely be influenced by the fiscal discipline of each member state, which is correlated to the prevailing political regime. The ECB cannot fund a member state but it needs to manage effective interest rates across the union and policy needs to be designed to that effect. The ECB can also influence the level of cross border debt to either discourage a member from leaving the currency union, or defuse the impact of such a member exit. The risk of a member exit is negligible at this point but cannot be ruled out in future.

The ECB meets in a couple of days and it will be interesting to see how Mr. Draghi communicates policy. What he wants is an economy strong enough for expansionary policy to be retrenched, if nothing else so it can be deployed in the next inevitable crisis. His hope is that the EUR retreats and provides some latitude for easing back on accommodation. He may try to talk down the EUR by sounding more dovish. At some stage he will want to stop expanding the balance sheet, maybe even shrink it. And he will need to raise rates into positive territory. (A one-time boost may result from bank lending before rising rates actually act as a brake.) At some point he will want to be more hawkish while sounding more dovish. The days of central bank signalling and clarity may soon be over. As ex Fed Chair Greenspan once said: if I turn out to be particularly clear, you’ve probably misunderstood what I said.