Global Trade War. Episode II

The Trade War continues. Since 2011, the Obama administration has been actively pursuing a program of reshoring.

http://agmetalminer.com/2015/01/22/obamas-manufacturing-centric-state-of-the-union-youll-never-hear/

Donald Trump’s agenda only seeks to bolster or exacerbate an existing trend. As global growth slows, every country seeks to become more self-sufficient and insular. Trading nations and those with a small or ageing population do not have the back stop of domestic consumption, and will suffer. Populous regions will seek to tap domestic consumption and investment as sources of growth. The strategic responses of the various regions are already becoming clear. China is a prime example with a stated objective of being more reliant on domestic consumption and less dependent on exports.

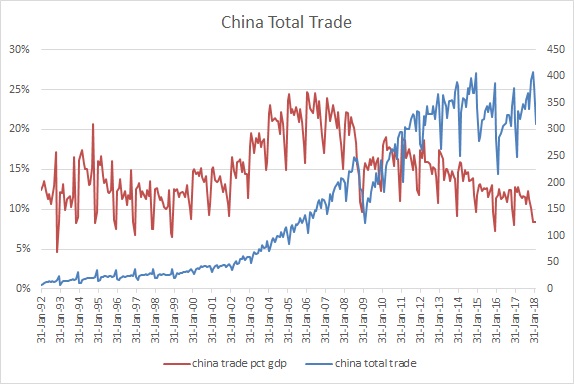

In China, total trade, here taken to be imports plus exports, have stalled and as a percentage of nominal GDP (ignoring inflation base effects), peaked in 2007 and has since been declining.

(data source Bloomberg)

The decline in trade has also brought with it a decline in manufacturing, as factories facing a foreign export audience are wound down and new ones facing a domestic audience are established. Such a decline has had a transitive impact on industrial commodities.

2016 was a year of recovery in manufacturing, a recovery that has extended well into 2017. This is likely a rebound due to the differential times in decommissioning old, export facing assets, and building new, domestic facing ones. The rebound has reversed the decline in manufacturing and commodities. A growth rebound also impacts demand for imports and reverses the decline in global trade. However, this is reactionary rather than causal. As the world’s productive assets settle into a new equilibrium, trade will stabilize at a lower level. If countries like the US under Trump accelerate protectionist policies, trade could resume its decline. In any case, lower trade is inflationary, ceteris paribus.

The fact that inflation is weak is all the more concerning in the context of reduced trade. It suggests that median output and income is weaker than mean (average) metrics. This could likely be due to a skew in the population for output and income data. In fact it supports the anecdotal evidence that wealth and to a lesser extent income inequality is acute in the developed nations.

The Trade War hypothesis is part of a more general and pervasive adversarial world. We see examples of this in the failure of the Accord de Paris, Brexit and the perceived Siege of Britain, protectionism in the US, Chinese policy to maximize FDI and minimize ODI (which is the investment analogue to trade war), China’s belligerence in the South China Sea, to name but a few.

In such environments, self-sufficiency is a sound strategy, provided one has the resources. Countries lacking in land, resources, labour and knowledge, will have the most difficult run of it.