A decade on from the Great Financial Crisis and all is well. Multiple rounds of extraordinary monetary policy campaigns have boosted asset prices and stabilized economies across the world. Intermittent turbulence from Europe (2011), Greece (2014), and Brexit (2016) have failed to derail the recovery.

The political landscape is changing as well with the rise of the Far Right in Europe, newfound stability in India and Japan, Brexit, nationalism in the US, and China under Xi, still not well understood. Social media have brought people together to share their divisions and create a more polarized world. Inequality seethes beneath the thin ice of the status quo.

Strides in technology make today seem like the science fiction of only a decade ago. The promise and threat of Artificial Intelligence beckons. A post scarcity utopia looms in the distance threatening dystopia on the way.

The most effective way to invest is to start early and keep it simple. Start with maximum tolerable risk and decrease the risk you take over time. Start early because you will need time to make up for mistakes, time to compound returns and patience for investments to mature. Trading tends to be more profitable for your broker than for you. And then keep it simple. Complexity works for specialists whom perhaps you may wish to hire (by investing with them), but this is more luxury than necessity. Common sense, patience, and a healthy disconnect from emotion are necessities.

Without the benefit of time and a long runway, we face today, fairly good fundamentals, synchronized growth, the beginnings of central bank policy normalization, a slight lull in the political agenda but expensive asset prices.

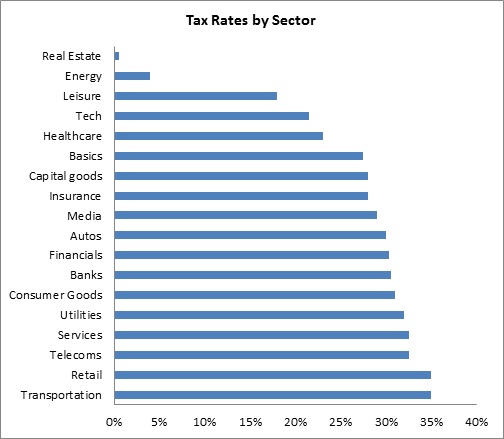

In the US, the pro-business President has struggled to get any policy passed despite Republican control of House and Senate. A significantly pro-growth tax reform package is the Republicans’ only hope of showing progress for the year. Otherwise, growth is robust, sentiment buoyant, inflation conspicuously absent, and in markets, equities are on the expensive side and credit spreads are as tight as a drum. The Fed is already on its 4th rate hike, is almost certain to hike again in December and has signalled 3 more hikes in 2018, something markets place a less than one third probability of happening. The market has been right in the last few years in being sceptical about the Fed’s hawkish intentions but is likely to be wrong this time. The Fed appears determined to normalize both interest rates and its balance sheet.

Some risks surround this policy normalization. Inflation has been weak, partially from weak energy prices but also at the core. Energy prices are on the rise but core inflation has been chronically and inexplicably weak. That said, we believe that the relationship between interest rates and inflation, at these low levels and at a turning point, could have anomalous effects, namely that raising interest rates could lift inflation. This finds some basis in the Neo Fisherian view as well as some microeconomic effects of cost of capital. From a liquidity perspective there is the risk that as QE inflated markets more than output and prices, perhaps the retraction of QE or quantitative tightening (QT), might have the reverse impact. This should also counsel caution on emerging markets exuberance as liquidity can drain from anywhere due to open markets and capital mobility.

A reluctant and boring consensus is building that returns from US equities should moderate to circa 5% p.a. over the next two to three years. The outlook for credit is less optimistic given where spreads are, slightly over 3% OAS for HY and 1% for investment grade. Taking into consideration duration, the outlook for bonds is not very rosy indeed. There are, however, pockets of potential if not outright value. Mortgage bonds and CLOs remain attractive but sourcing and selection are key in these highly idiosyncratic markets.

Until recently Europe has been the most problematic major developed economy. Weak peripheral sovereign balance sheets, Greece, Far Right populism, under capitalized banks, and then Brexit serially buffeted the European economy. More recently we have seen a resurgent economy, still with no inflation, but improving PMIs and sentiment, and more buoyant stock and credit markets. A weak EUR has played a part in this prosperity. How long can it last?

The longer term picture presents headwinds. The single currency is inefficient at clearing factor markets leading to unemployment and underemployment, and leads further to misallocation of resources. Inflation should pick up but thankfully has not. Unemployment has receded but is still painfully high in places (over 17% in Spain.) There is common monetary policy but alignment of fiscal policy is still a challenge.

Brexit looms. Both the UK and the EU have appeared to weather the impact of Brexit, but only because it hasn’t happened yet. The EU will lose its largest trading partner and its pro-business lobby. The UK will lose an arm and a leg.

The rise of the populist Far Right did not die with the French elections earlier this year, they only went to ground. Despite Le Pen’s and Wilders’s losses, both expanded their parties’ representation and influence. In Germany, the AfD, previously unrepresented in the Bundestag managed to win over 12% of the vote and 94 seats. Elections are due in Italy in 2018. More immediately are regional elections in Spain where the Catalonian will try to legitimize its secessionist plans.

In the shorter term, the momentum is strong. The ECB’s exuberance was premature and it was forced to extend QE till 2018, even if at half strength. The ECB is likely to remain in accommodative mode for the foreseeable future, impacting the EUR adversely, and stocks and credit positively. One area of particular opportunity is bank capital. Tightening regulatory standards, IFRS9, Basel IV, and ECB NPL treatment, will be a tailwind for subordinated capital (and a headwind for equity).

For equities in general, the continuing easy monetary conditions, steady growth, and lack of political noise coupled with lower valuations relative to the US will support markets, especially if the EUR is also weak on interest differentials. The outlook for credit is less positive given how tight spreads have become but general conditions remain benign.

India. With almost as many people as China, two thirds of whom are of working age, a per capita GDP (at PPP) 2.3 times smaller and a nominal GDP nearly 5 times smaller than China’s, India’s potential for growth is significant. The problem is realizing that potential. The political stability and the popular support enjoyed by Prime Minister Modi, whose party in 2014 won the first simple majority in 30 years, could help unlock this potential. The reform agenda has been packed and the pace frenetic. The implementation of GST replacing local and state taxes is analogous to the creation of a common market like the EU. The demonetization effort while bringing long term gains has short term costs in the form of slower growth as the informal sector is assimilated. The Indian economy is currently growing through consumption and government expenditure but private sector investment has been moribund. To animate private investment the government needs to clean up the banking system which has accumulated a growing mass of non-performing assets. A new insolvency and bankruptcy code was established last year which the RBI is encouraging the banks to use aggressively. Only when NPLs are addressed can the recapitalization of banks occur which will give them the capacity to finance the economic growth potential in India. In the meantime, government investment in infrastructure, in road and rail, telecoms and the financial system continue apace, investments which address directly one of the main difficulties in India. In the short term there will be volatility as rising oil prices and the large agrarian sector of the economy faces more uncertain monsoons arising from climate change. This will impact inflation and RBI policy as growth claws back from the demonetization and implementation of GST. In the long term if India just catches up part of the way with China, its growth and development will increase significantly.

Japan. Japan is a country with poor macroeconomic conditions and strong microeconomic fundamentals. It has one of the highest per capita GDP levels, nominal or PPP, it is one of the most modern and technologically advanced countries in Asia, the current government is stable and Abenomics has reinvigorated Japan’s economy and boosted sentiment amongst consumers and businesses. Balancing this is a rapidly ageing population the result of falling birth rates and rising life expectancy, a national debt which is over 2.5X GDP, a central bank that is increasingly the lender of last resort to the sovereign, albeit indirectly, and a propensity for propping up inefficient zombie companies which sustains overcapacity and suppresses inflation. Where there are problems there are opportunities. Japan’s ageing population and shrinking labour force encourage private sector solutions to problems which the rest of the developed world are facing or will soon face. Japan has an oft overlooked technology sector which is domestically focused and which foreign investors struggle to navigate. Often these are small and mid-cap companies which are little covered by sell side analysts and little known outside Japan. The advantages of understanding and investing in these areas is not just the returns they might bring but the lessons they hold for the rich, ageing, developed world. Demographically and fiscally, Japan could well be our future. Opportunities exist in companies at the centre of labour reform, technology, gerontology and healthcare. But beware as over 80% of the companies in the benchmark indices are old economy laggards.

China. At the recent 19th National Congress of the Communist Party, President Xi’s Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era was enshrined in the constitution, solidifying the President’s position in the party and China’s history. While this appears to be the building of a cult of personality, China is complicated. China intends to consolidate its progress and standing international community. It seeks to integrate itself into more global institutions and standards and engage the world in generally accepted terms. Of course it aims to shape those terms but gone are the days when China would go it alone. That distinction appears to be the preserve of the US. China builds bridges, as the US attempts to build walls. In its path to maturity and international integration, China precipitates a number of contradictions, not unique to China but certainly of note. China wants to open its markets and capital account but at the same time wants to retain control over the path of liberalization. The President seeks to inculcate rule of law over rule of party, but seeks to consolidate his control over the institutions and policies that shape China. Asia is replete with strongmen but successful ones have tended to co-opt rule of law to their side, cosmetic or real, rather than rely on outright repression.

Within more practical time frames, growth is expected to slow for no other reason than the size of the economy. A 6% growth rate in the next 3 years would not surprise. The surge in credit creation over the past few years will need to be managed carefully. There are concerning signs that regulators may not have this completely under control. As banking liquidity growth has moderated, total social financing, a measure that includes the shadow banking system indicates continued growth. The PBOC will continue to tinker (or meddle, if you are a sceptic), to maintain a neutral macro stance while redirecting credit to direct growth and leverage as it sees fit. One Belt One Road will need a lot of credit to finance its investment. Local governments will be encourage to continue deleveraging. The profusion of conduits (LGFVs, trust loans, wealth management products) will be challenging to regulate and modulate.

The economy has already become less export dependent, a stated objective some 5 years or more ago, and more domestically oriented. This is a piece of risk management despite the continuing drive to build bridges to deal with a more protectionist USA. The US has been more protectionist since well before Trump when reshoring was championed by former President Obama, as evidenced by campaigns such as SelectUSA and Manufacturing USA. Export sector companies globally remain at risk as trade as a percentage of GDP has fallen steadily over the last 5 years.

In spite of potential for reduced trade, China is a populous country with enough resources and technology to be relatively self-sufficient. Its growth rate would be quite high for an economy of its size and complexity which would provide support for equity markets. In the more immediate term, the relative outperformance of the HK H share market relative to the onshore A share market could be unwound. Local A shares look better value.

As always, there are threats we have chosen to ignore, at least for now, mostly for good reason. We highlight such a threat, which is an academic oddity. The past decade has been characterized by economic recovery, strength even in some quarters, coupled with low inflation. To some this has been a concern and to central bankers it is a puzzle. Aggressively cutting rates and depressing bond yields has had little impact on inflation. This is even more acute considering the large weight in the CPI of owner’s equivalent rent, a non-cash flow item. Central bankers operating according to the Taylor Rule when in fact a Neo Fisherian process exists would quickly converge to the zero lower bound, as observed in practice. If the Neo Fisherian model is valid, a gently path of rising interest rates would encourage inflation and a central bank continuing to operate under the Taylor Rule could push inflation steadily higher. Markets are not prepared for this and have an overly sanguine view of inflation and interest rates. The consequences for fixed income investors and for borrowers would be serious. The impact could also be exported through FX as countries try to maintain some stability in their exchange rates, resulting in rising cost of credit. There would be consequences for developed market equities as well as valuations are already stretched and low rates are required to justify elevated multiples.