How High/Low/Long Can You Go?

Can US equities sustain a bull market or even current levels without central bank support? Prior to unconventional monetary policy, the last 2 bull markets lasted from 1995 – 2000, and 2002 – 2007, or roughly 5 years in each case.

What is not so easy to explain is why equities and corporate bonds have both rallied as much as they have when the Fed is no longer expanding its balance sheet and has undertaken a number of rate hikes. This stark acceleration in valuations began in early 2016 and for equities at least, has yet to find a top.

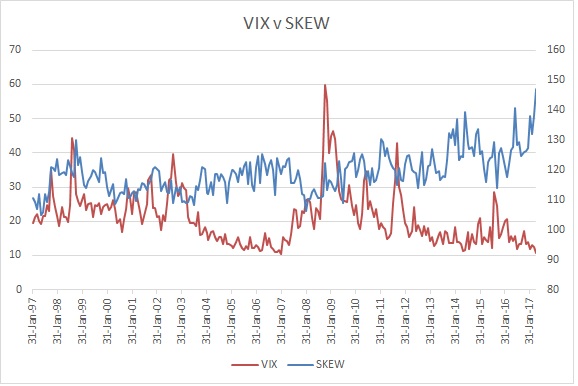

Source* Bloomberg

We ask a number of questions.

If GDP growth fails to sustain current rates or if it weakens, what policy tools can be deployed?

The Fed has never before kept rates this low for this long. While it has made 3 rate hikes to date (12 June 2017), Fed Funds stands at 1%, which was the lowest level in the last cycle before it started hiking in 2004. To cut rates, the Fed has first to raise rates and it has to raise rates with sufficient care that it does not precipitate a slowdown. With growth rates at these tepid levels and interest rates at 1%, the Fed has not much room to manoeuvre.

The Fed began with a balance sheet size of less than 1 trillion USD before the financial crisis in 2008. Multiple rounds of QE later the balance sheet stands at nearly 4.5 trillion USD. Financial conditions and growth have stabilized to the extent that the Fed now contemplates the gradual normalization of its balance sheet. Quite what the normal size of the balance sheet and how gradual the path to normalization should be is not known. The Fed has signalled that it is considering the question and could begin some sort of normalization later this year.

The Bank of Japan’s experience is comforting, in a way. From 1997 to 2005, the BoJ increased its balance sheet by a factor of 1.7X. It was able to reduce its balance sheet by 33% when the 2008 financial crisis struck. Thereafter it increased its balance sheet by almost 4X and it hasn’t stopped. Over the last 20 years, the BoJ has increased its balance sheet size by 7.7X. The one time it shrank it, a crisis emerged, admittedly not of its own doing, within 2 years. The BoJ continues to buy JGBs and has added equity ETFs to the shopping list and does not look like stopping soon. Yet throughout the BoJ asset purchases, rate cuts, and the public debt to GDP rising (from 50% in the early 1980s, to 234.7% currently), no great calamity has been suffered by Japan, except over 20 years of disinflation, and stagnant wages. Unemployment is chronically low, inflation has not risen, the currency has been relatively stable and indeed inexplicably strong, corporate profits relatively robust and bond yields have been remarkably stable.

Of course the Fed would like to achieve better than to limp along and claim that incapacity is victory over death. The US situation may not be as tractable given the open economy and open markets, especially the internationalization of the USD. The BoJ has maintained control over the interest rates because it is currently the proud owner of nearly 44% of the national debt.

Besides monetary policy fiscal policy can be engaged to support a flagging economy. However, it is often necessary to engage both fiscal and monetary policy to tackle flagging growth. Fiscal policy needs to be financed, and the US national debt, while small by Japanese standards is some 104%, which puts limits on how much it can borrow and spend before the Fed will need to help cap debt service costs.

The ECB has a repo rate of -0.25% and the BoJ has a policy rate of -0.10%. Most Eurozone countries are close to or beyond their budget deficit thresholds making fiscal policy difficult at best. The BoJ as noted earlier, is special. Neither region can sustain much negative surprises as policy is already acutely accommodative. For the BoJ, the time at which it may need to cancel some of the JGBs it holds may be drawing closer.

Do asset prices make sense?

This is a very wide and general question. Let’s begin with a few specific examples.

Does a yield of -0.75% make sense for 2 year German bunds?

How about Italian 2 year bonds at -0.36%, or Spain at -0.36%, or France at -0.56%?

Germany probably needs higher interest rates, certainly more than the -0.36% EONIA rate, but what about Italy and Spain? If we look from the point of view of what policy rates each country requires, then the periphery needs low rates to support their economies while Germany does not. If we look from the point of view of credit quality, then peripheral rates should be higher to compensate for default risk.

Does a current PE of 22X make sense for the S&P when it has historically been trading at around 18X? The S&P has only traded at or above 22X during late 1987, 1992 – 1993, 1997 – 2002, late 2009. The period in 1987 ended with a sharp correction. The period 1992 -1993 saw decent returns of circa 5% – 6% annualized. The period 1997 – 2002 saw a return of about -4.5% to -5% annualized. And in 2009, the market topped out at the end of the year and traded range bound till late summer 2010.

It is interesting to note that Nasdaq has tended to trade at high valuations, ostensibly due to the high expected growth rates. On a historical basis, Nasdaq trading at today’s 26X is less over-valued than the S&P trading at 22X. In the years prior to 2008, Nasdaq maintained a steady valuation of between 30X – 33X whereas the S&P traded at between 16X- 18X.

Does the Baa spread of 2.2% make sense given the economic cycle and credit fundamentals? The Baa spread has traded as low as 1.5% in 2007 just before the mortgage crisis. An over accommodative Fed drove spread tightening from 2002 to 2007 before the mortgage crisis all the way up to the demise of Lehman caused spreads to spike to as much as 6.2%. Corporate leverage rose from 2014 to 2016 but has since declined. Default rates remain well contained and recovery rates have stopped deteriorating. It seems that credit is expensive but not egregiously so.

How about leveraged loans? Loan coupon spreads have compressed to below 4% and 60% of the market trades above par. On average, performing loans are yielding a paltry 4.7%. While default rates are 1.3% having recently peaked at 2.17% in mid-2016, loan repricings have topped 200 billion in Q1 alone and could further dampen returns. Loan spreads were steady at 4% for most of 2014 then rose sharply in 2015 into Q1 2016. Since then spreads have come in well below the 2014 levels making the asset class definitely expensive.

Bond spreads are tight as well but whereas the continuously callable nature of loans places a limit on the loan price, so that significant proportions of loans trading above par are a clear sign of overvaluation, such technicalities do not exist for the bond market. We therefore ask if 2.4% spread between Baa corporate credit and treasuries makes sense. Surprisingly the answer is, while the bond market is not cheap, neither is it too expensive. It can be described as moderately expensive. Low end investment grade spreads ranged from between 0.70% and 3.05% from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. The low end of spreads was about 1.4% from the 1980s to 2007, before the big spike in spreads as the mortgage market collapsed. Post 2008, spreads have been trading between 2.1% to 3.5%. In this recent context, current spreads of 2.4% appear tight. However, risk in the financial system has been addressed and reduced, banks are better capitalized, risks are more ring-fenced and contagion risk diminished. Moreover, despite slow growth, corporate balance sheets have improved, companies are profitable again and growth has become more broad-based. One might assert that a central tendency of 1.8% – 2.0% is reasonable in which case the current market is moderately but not acutely expensive.

Parting comments:

The current flow of economic data seem to indicate a world of steady if moderate economic growth on the one hand and of high if not excessive asset valuations on the other. Seen in commercial and economic terms, markets appear to be properly priced in the main with a few exceptions. High valuations do not cause market corrections but imply deeper losses if and when they occur. Exogenous forces could cause a market correction, factors such as politics and policy. The acute inequality faced by many countries leads to less stable governments and less stable social contracts.